The Benefits of Not Fishing in a Crowded Pond

Investing in farmland as an asset class is not well understood and while I believe that is part of what makes it such a unique opportunity, it probably requires a bit of explanation. In order to help investors understand the benefits of owning farmland, I have been writing very long blog posts but the reasons for owning the asset class are best summarized in the list below:

- Investors want and need diversification (i.e. uncorrelated assets)

- Many alternative assets (e.g. private lending, private equity, real estate, etc.) try to provide diversification but most are levered to the economic cycle and won’t likely provide that diversification over the full cycle

- Unprecedented monetary policy around the world has left financial assets very expensive relative to real assets

- It is estimated that approximately 1.5% of farmland globally is owned by investment funds; meaning as an asset class it has not seen returns driven by excessive capital. It also means that unlike most other asset classes, investors aren’t competing with other investors flush with cash (we’re not fishing in a crowded pond)

- COVID-19 has underlined the importance of defensive assets, and the importance of short supply chains (Ontario farmland is a relatively short truck drive from approximately 25% of Canada’s population and millions more south of the border)

- It is a defensive asset but unlike most defensive investment options, it has not been bid up by investors using leverage which has pushed valuations higher

- Unlike many businesses that are threatened by disruption or displacement from technology, farmland has benefitted from innovation with efficiency and production gains accruing to the owner of farmland

Ontario farmland is attractive for the following reasons:

- Strong historic returns

- Returns have been uncorrelated to equity or debt markets (correlation to the S&P 500 over the past 100 years has been 0.1169)

- It is a very defensive asset since up to 200 different crops are grown in the region, making it less vulnerable to weakness in commodity crops

In past notes I showed how valuations have risen for many financial assets as more and more capital rushed in. The valuations also included the use of more debt as rates came down and investors became increasingly complacent during the longest economic cycle in history. As investors we like to think we have done better analysis than others and identified value where others have missed it. But the reality is much of the success of an investment is based on being an early investor and recognizing the value before others take notice.

It’s Harder to Invest in a Crowded Market

A while back, I was reading an article about Gerry Schwartz, a Canadian “private equity” investor, who was reflecting on his career. He talked about how when he started in the business in the 1970s, the total amount of capital committed to private equity, globally, was about US$300 million. Today, there is US$2.5 trillion looking for deals and his firm alone is sitting on more than US$2 billion of dry powder (capital they need to put to use). He went on to say, “it is a very, very difficult market” suggesting many private equity fund managers are willing to risk overpaying to buy businesses because they are “desperate to get invested and move on the next fund raise” (Link to article). In other words, there’s too much money chasing after potential private equity targets, making it less likely to find a good deal and generate outsized returns.

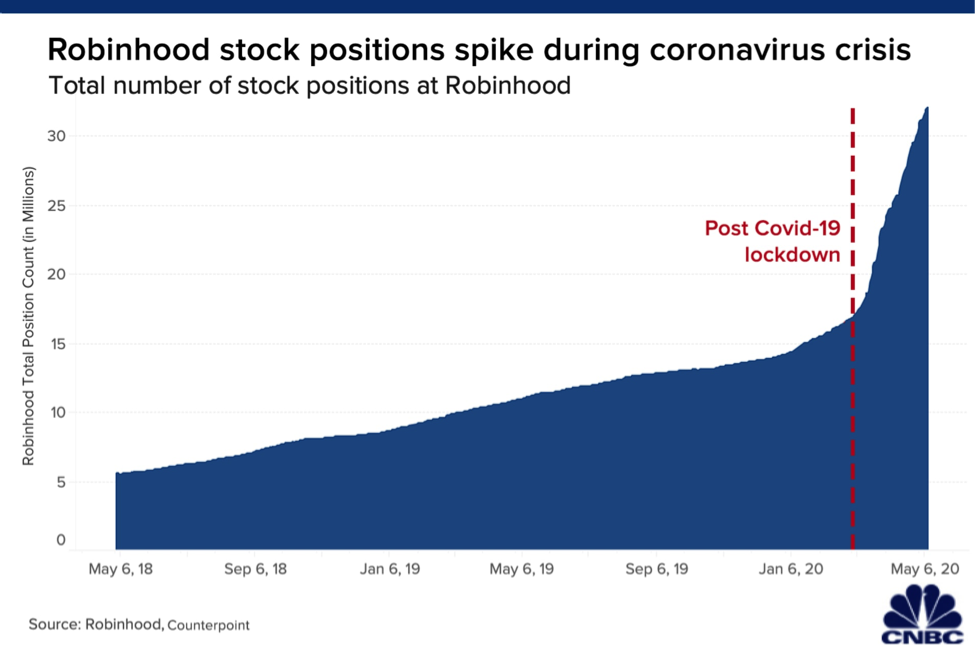

It seems being the smartest person in a crowded room isn’t as much of a benefit as you might think when it comes to investing. In fact, it’s best to avoid the crowd. Just ask Warren Buffett. At the recent Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting, Buffett said he is unable to find much value in the market and was sitting on $137 billion in cash. Since then, he has proceeded to actually sell some of his positions and raise even more cash. Funny thing though, just as Warren has been selling and raising more cash, the retail investors have come rushing in. There has been a spike in new accounts at online brokers, which according to CNBC, shows that young and inexperienced investors saw the coronavirus downturn as an entry point into the world of investing. The major online brokers saw new accounts grow as much as 170% in the first quarter, when stocks experienced the fastest bear market and the worst first quarter in history. According to one e-broker, the new accounts proved to “skew younger” over the last quarter. Robinhood – a millennial favoured trading app – saw a mind-blowing three million new accounts in the first quarter (Link to article).

A recent Barrons article titled “Day Trading Has Replaced Betting as America’s Pastime” described how some these trading platforms have taken to “permitting trades of fractional shares, letting small guys get a piece of highflying stocks priced in the hundreds or thousands of dollars” (Link to article). The point is that while the novice investors have come rushing in to buy in unprecedented numbers, the supposed experts haven’t been able to find value. Maybe it’s too much “novice” money (I’m being very kind here) that is driving up valuations to levels that leave some of the world’s greatest investors sitting on their hands. When that much unsophisticated money shows up bidding on the same assets, it is inevitable that valuations become expensive and returns going forward will likely require more “unsophisticated” investors to bid them higher.

The same dynamics being experienced by Canadian “private equity” investor, Gerry Schwartz, who suggested the business was a lot easier when he was one of only a few people looking to buy private companies, are impacting Warren Buffet as well. Interestingly, Buffett hasn’t been able beat the S&P 500 since the financial crisis, the longest such streak of his career. I’m sure it’s just a coincidence that central banks began their QE programs following the crisis, which allowed for indiscriminating purchase of assets (and I would argue began the impairment of true “price discovery”). The point is that while both are widely acknowledged as brilliant investors, their ability to make good investment decisions has become challenged. The investments available in both public and private equity markets are all being bid upon by a larger pool of increasingly unsophisticated capital. The opportunities that existed before in private equity are now swamped with offers from other private equity managers with lots of cash that they must deploy. In public equities, unsophisticated investors have entered the market and bid up prices with little analysis (replacing betting?). Both of these individuals are now fishing in very crowded ponds and competing with less disciplined investors.

Which Brings Us to Farmland

While it is difficult to get precise numbers, I’ve seen estimates that suggest there are 3.95 billion acres of farmland in the world and that farmland owned by investment funds amounts to some 50 million acres. That would suggest less than 1.5% of farmland globally is owned by investment funds. But even at twice that number, farms remain largely in the hands of farmers and haven’t seen valuations distorted by access to cheap debt. In fact, other farmers, who hardly have access to easy money, purchase an overwhelming majority of farmland. Which means the farms must trade at fundamental values, since an actual operator is purchasing it with little available leverage.

While we believe southwestern Ontario farmland is the best farmland in Canada and among the best in the world, the farms are, on average, smaller. Meaning it isn’t easy for large institutions to find adequate amounts given the size of their capital and their need to deploy enormous amounts of money. I’ll use the comparison to private equity because there are a number of similarities. In the early days of private equity, there were a number of small private companies that could benefit from capital and skilled management, but there was a very limited amount of capital relative to the number of opportunities. That set-up meant private equity investors enjoyed great returns for many years. Private equity managers had their selection of investment opportunities and ample opportunity to make improvements to increase the value. Today, private equity has attracted so much capital that they are now chasing after investment opportunities in the public market that are already professionally managed and whose returns have been driven by the same factors driving all financial assets (higher valuations and greater use of debt).

Today the investment opportunity in farmland is much the same today as it was for private equity in the early days. The demographics of farming are older, with a great number of farms in need of more attention and capital. Meaning a skilled buyer has ample room to surface additional value. Given the relatively low percentage of financial owners, the only buyers of farms have been farmers, meaning fundamentals and not financial engineering have driven price increases. With less capital chasing after farmland, there should be lots of room for a smart buyer to add value, just like Gerry Schwartz did.

The purpose of these notes is to explain the opportunity available in farmland. I believe that being a smart investor involves finding a situation where you will have the wind at your back. A proven asset class, where the opportunity to optimize assets exists and where very little capital has yet to be committed are the sorts of conditions I would characterize as a pretty good wind at our back.

Written by AGinvest Senior Vice President of Business Development, Anthony Faiella. To reach Anthony please email Anthony.Faiella@AGinvestCanada.com

This information does not constitute financial or other professional advice and is general in nature. It does not take into account your specific circumstances and should not be acted on without full understanding of your current situation and future goals and objectives by a fully qualified financial advisor.