It is said that Einstein called compound interest the “Eighth Wonder of the World”. The basic premise is that once you have earned interest on your money, that interest is now earning you interest. Your wealth compounds in its rate of growth because you’re generating returns on returns already earned.

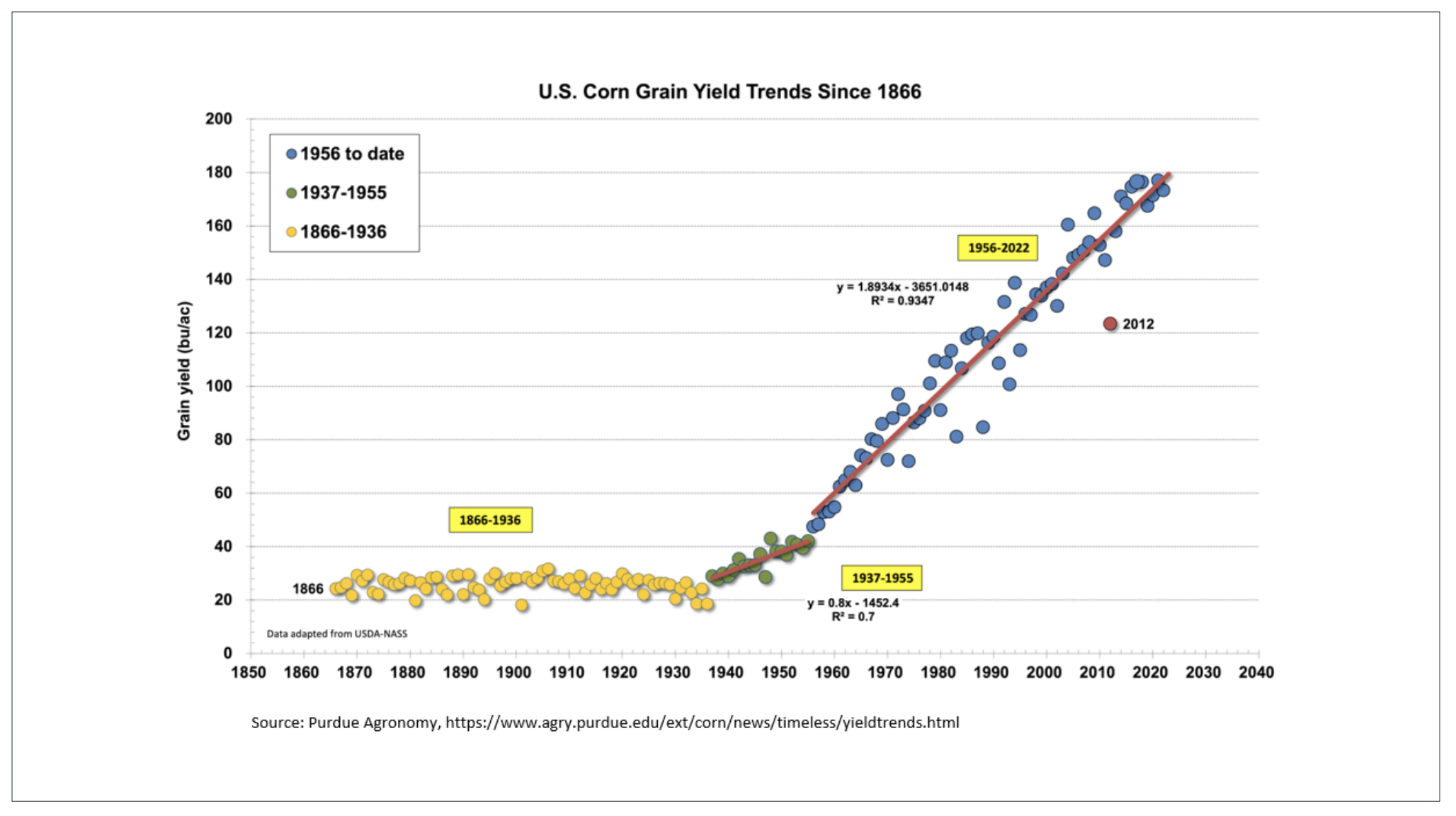

The idea is to avoid any negative returns that bring down the value of your money, which sets you back all the more. While ours is not a story of interest income, it is most definitely a story of compounding returns. Those returns really commenced during the 1950s, when mechanization of farm equipment and

subsequent innovations began to make farms continuously more productive and more efficient. Since

then, the pace of innovation has increased resulting in yields and efficiencies that have built on prior

gains. The gains that were occurring in the fields coupled with food price inflation resulted in steadily

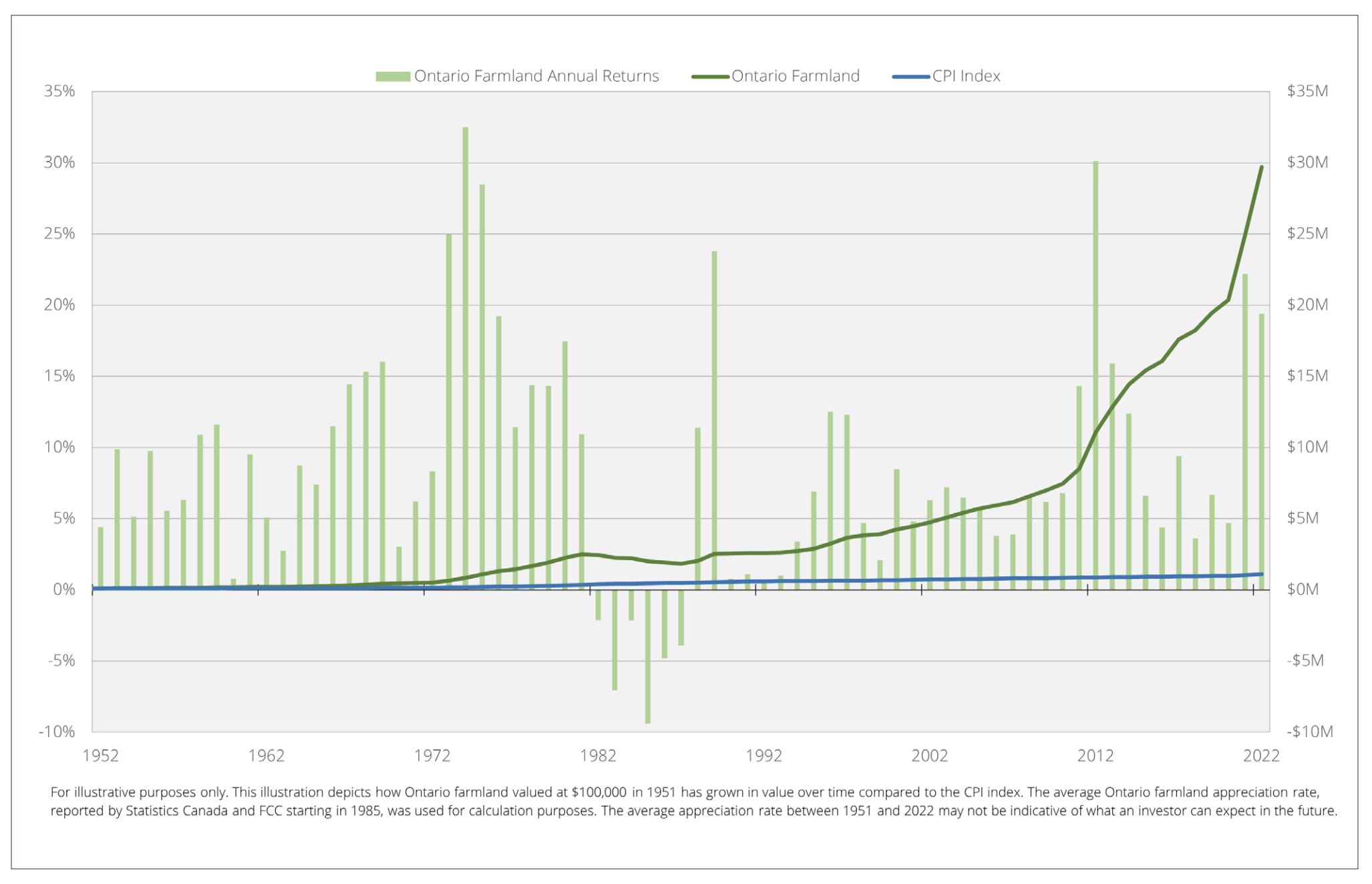

increasing values for farmland. This meant that with only a few exceptions, the value of farmland

compounded almost annually. We like to use the analogy of buying an apartment building or commercial office tower and every few years, that building has an additional floor. Over a period of many years, that building is much larger and generates a lot more income for its owner.

The gains built in farmland are fundamental and have proven to be permanent over more than seven decades. The value of farmland is determined by the yield it produces, the cost to produce that yield and the prices achieved on that yield.

Warren Buffett has talked about the “Snowball Effect” as a metaphor for the compounding of wealth. He has also talked about the importance of owning real assets, especially assets that can’t easily be replaced or duplicated. In 2009, Buffett bought Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad for $26.5 billion. A railroad such as that one is increasingly difficult to replicate with each passing year, and every train that crosses over its tracks must pay a toll. At the time, Buffett said in an interview that he’d paid a steep price to own a business that would benefit his company over the next century.

“You don’t get bargains on things like that” Only five years later, the company was generating a lot of free cash flow and had already sent more than $15 billion in dividends back to parent company Berkshire. We think of farmland in much the same way. It is an asset that can’t be duplicated or replaced and every year it produces returns for its owners. Those returns keep pace with inflation because food demand is inelastic. There is little change in consumption when food prices rise.

After more than 70 years of returns, where innovation meant gains were built on top of existing gains and returns were compounded, farmland has generated spectacular returns. The Snowball Effect that Buffett talks about can be seen in the value of farmland, so it is no wonder he has been such a proponent of owning farmland. The Compound annual growth rate for Ontario farmland over the past 71 years has been 8.2%. In other words, the annual gains that have compounded the value of previous gains, have occurred at 8.2% over more than 70 years. The result of such high consistent returns can be seen within the chart on the previous page. The value of $100,000 invested in 1950 would be worth approximately $30 million today if you had owned a portfolio of farmland and realized just the average return on Ontario farmland.

When we look forward to the innovations being developed for farming, we can see technology that will make farming even more cost efficient and productive. Those gains should continue to accrue to farmers and farmland owners. We believe building wealth, especially in real terms (net of inflation) is about owning an asset that is essential, can’t easily be replaced and generates revenues that keep pace with inflation. Ontario farmland has been, and continues to be, an exceptional asset for building such wealth.